GCP Cost Management: BigQuery

TL;DR:

LIMIT 10does not save money (you are billed for the full scan).- Partitioning by

TIMESTAMPcuts query costs. - Don't stream raw events. Use Redis to aggregate data before inserting into BigQuery to save on query overhead.

Table Of Contents

- Introduction

- BigQuery

- Data Preview

- Partition + Cluster

- Scheduled Queries

- Calculate Before Insert To Save Cost On Data Scans

- Conclusion

Introduction

The cloud is only cheap if you treat it like a finite resource. In this article series I am going to cover that to watch out for in most popular GCP Services and where are their gotchas to help you save on your GCP bill.

BigQuery

BigQuery is likely the most used service on GCP. It feels like a breeze to load datasets ranging from megabytes to terabytes effortlessly. But because it scales so well, it is incredibly hard to mentally cap your usage, because when writing queries and querying large datasets performance degradation is only noticed when query times start to grow.

Does LIMIT 10 save BigQuery costs? Short answer - No.

There is a common misconception that adding LIMIT 10 to a query saves money. I learned this the hard way just by watching the "data scanned" metrics on my own projects. The query cost is based on the data read, not the data returned. If you scan a terabyte to find five rows, you pay for the terabyte.

- Avoid

SELECT *. BigQuery uses columnar storage; only select the columns you actually need.

Data Preview

- Preview data in the console.

- Preview data in cli with

bq head

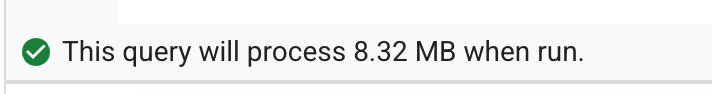

Price Queries Before Running

- Look at the validator - it tells you exactly how much data it will process.

- Pass the

--dry-runflag to see the byte count without executing.

Partition + Cluster

Partitioning splits one big table into smaller chunks based on a column value (usually a date/timestamp). BigQuery now supports 10,000 partitions per table (up from 4,000), giving you ~27 years of daily partitions. Partitioning cuts scans by 70-90%

Clustering sorts data within partitions by chosen columns, so queries filtering on those columns read even less data.

Back in the day, I was working on a project to track crypto price movements and try to correlate them with Bitcoin blocks in another database. I visualised everything in Grafana. As the dataset grew, the BigQuery spend started going up. But the dataset didn't grow in size by any significant amount to justify the spend. After digging into docs and optimisation tips, I found out about data partitioning and clustering. I partitioned by the created_at timestamp field. This reduced the data scanned/read by a significant amount.

If your partitions are smaller than 1GB, BigQuery takes longer to read metadata. This can hurt your performance. But if you are fine with slower performance but cheaper queries, by all means you should partition your table.

Scheduled Queries

It can be another cost trap. Before scheduling the query make sure it is scanning acceptable amount of data to serve the purpose.

What I like to do it to imagine if the table I am reading will grow in size 1000x. Will this be efficient enough to accommodate growth?

If not, then improve filtering or select fewer columns or take other action to mitigate this.

If you find your self running scheduled queries to calculate something every minute maybe calculating at run time would be better bet?

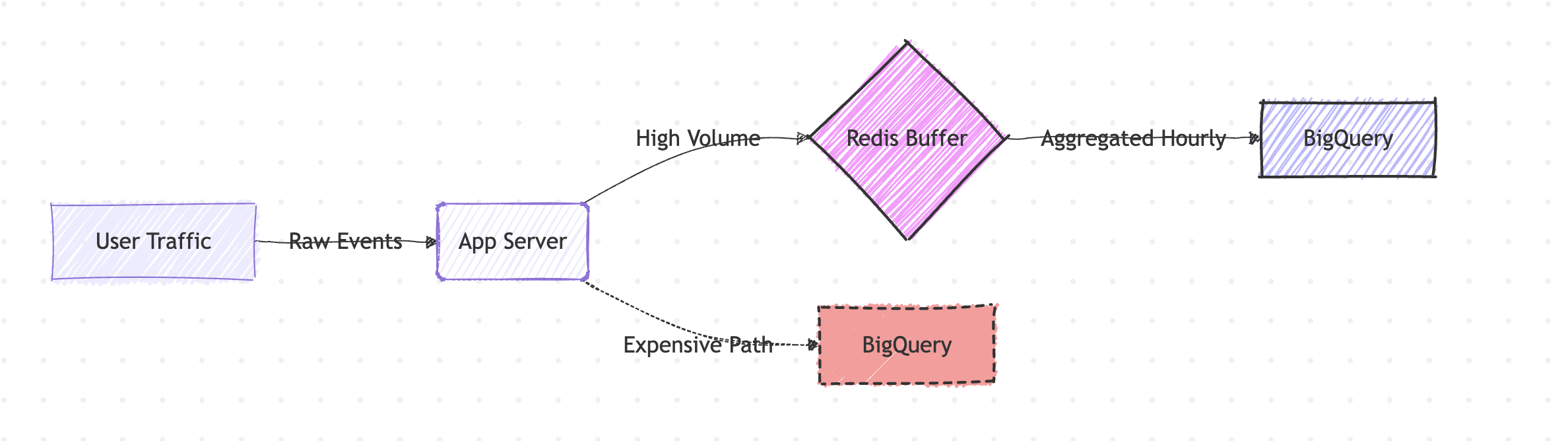

Calculate Before Insert To Save Cost On Data Scans

How frequently scheduled query should run? Need to calculate something every minute? Probably you'd be better off calculating those numbers at run time before data reaches the dataset.

Here is an example. Imagine you want to calculate page views per user, per hour.

99% implementations would result in following query and be scheduled.

SELECT

user_id,

TIMESTAMP_TRUNC(timestamp, HOUR) as hour,

COUNT(*) as page_views

FROM pageviews_table

WHERE timestamp >= TIMESTAMP_SUB(CURRENT_TIMESTAMP(), INTERVAL 1 HOUR)

GROUP BY user_id, hour

But the better practice would be to calculate at run time and flush the results to the BigQuery.

The following example is shown by leveraging Redis.

Redis is an open-source, in-memory data store known for its extreme speed and sub-millisecond latency. Here Redis serves as a high-speed buffer (or pre-aggregation layer).

async function processPageView(event: PageViewEvent) {

const hourBucket = truncateToHour(event.timestamp);

const key = `${event.userId}:${hourBucket}`;

await redis.hincrby('page_view_counts', key, 1);

}

async function flushToBigQuery() {

const aggregatedCounts = await redis.hgetall('page_view_counts');

await bigquery.insert('page_view_hourly_summary', aggregatedCounts);

// ...then clear the keys from Redis

}

The processPageView(event) grabs the event and increments Redis key. Then cronjob stores the data into the BigQuery by calling flushToBigQuery

Conclusion

BigQuery's power is also its trap: it scales so effortlessly that costs aren't a thing until the next billing cycle. The fixes are simple - partition your tables, preview before querying, and push aggregations upstream.

If you're dealing with high-throughput data streams, consider handling transformations and deduplication before data even reaches your warehouse. I explored this architectural approach in my Bitcoin to ClickHouse pipeline, where GlassFlow handles stateful processing to keep only clean, deduplicated data flowing into storage - a pattern that works equally well whether you're landing in ClickHouse or BigQuery.